Eddy Current

# Description

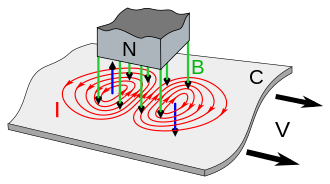

Loops of electric current induced in a conductor by a changing magnetic field per Faraday’s law of induction. Eddy currents flow in closed loops perpendicular to the magnetic field. Also called Foucault’s currents.

# Applications

# Eddy current brakes

Eddy currents create magnetic fields that oppose the magnetic field that created them (per Lenz’s law). This effect is used in several applications such as eddy current brakes for rotating power tools, brakes for railroad cars, or roller coaster car brakes.

# Eddy current testing

The Archer Piper wing spar AD (Airworthiness directive) uses Eddy Current testing to identify cracks in the wing spar in a non-destructive way

# How Does Eddy Current Testing Work

The process relies upon a material characteristic known as electromagnetic induction. When an alternating current is passed through a conductor – a copper coil for example – an alternating magnetic field is developed around the coil and the field expands and contracts as the alternating current rises and falls. If the coil is then brought close to another electrical conductor, the fluctuating magnetic field surrounding the coil permeates the material and, by Lenz’s Law, induces an eddy current to flow in the conductor. This eddy current, in turn, develops its own magnetic field. This ‘secondary’ magnetic field opposes the ‘primary’ magnetic field and thus affects the current and voltage flowing in the coil.

Any changes in the conductivity of the material being examined, such as near-surface defects or differences in thickness, will affect the magnitude of the eddy current. This change is detected using either the primary coil or the secondary detector coil, forming the basis of the eddy current testing inspection technique.

Permeability is the ease in which a material can be magnetised. The greater the permeability the smaller the depth of penetration. Non-magnetic metals such as austenitic stainless steels, aluminium and copper have very low permeability, whereas ferritic steels have a magnetic permeability several hundred times greater.

Eddy current density is higher, and defect sensitivity is greatest, at the surface and this decreases with depth. The rate of the decrease depends on the “conductivity” and “permeability” of the metal. The conductivity of the material affects the depth of penetration. There is a greater flow of eddy current at the surface in high conductivity metals and a decrease in penetration in metals such as copper and aluminium.

The depth of penetration may be varied by changing the frequency of the alternation current – the lower the frequency, the greater depth of penetration. Therefore, high frequencies can be used to detect near-surface defects and low-frequencies to detect deeper defects. Unfortunately, as the frequency is decreased to give greater penetration, the defect detection sensitivity is also reduced. There is therefore, for each test, an optimum frequency to give the required depth of penetration and sensitivity.